Migrating from VMware or Hyper-V to Vates VMS

Moving away from VMware or Hyper-V? Learn how to migrate to Vates VMS smoothly, cut costs, and regain control of your virtualization stack.

Most migration projects fail for one reason: they are treated like a purely technical conversion exercise.

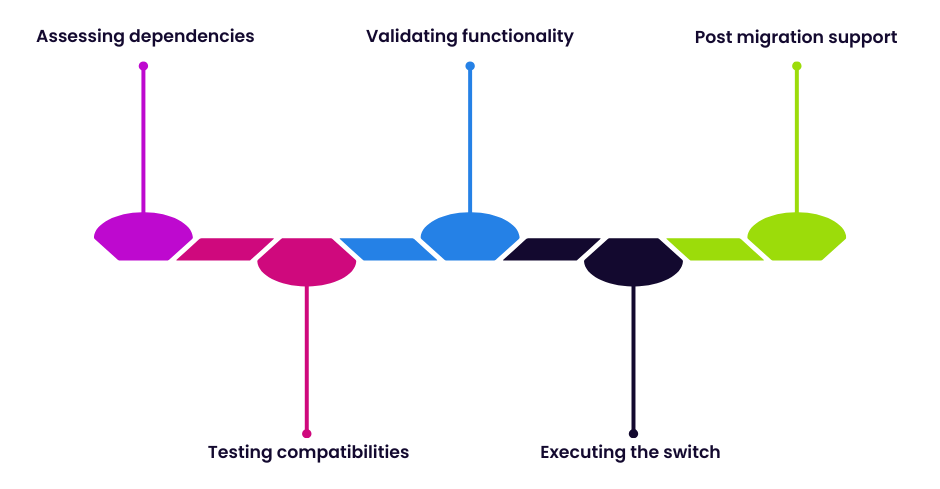

A clean move from VMware or Hyper-V to Vates VMS is not a single technical operation. It is a structured program built around three core pillars:

- Scope control (what moves first, what waits)

- Operational safety (downtime, rollback, validation)

- People and process (ownership, timeline, runbooks)

This guide is written for CIOs, IT managers, and infrastructure leads who need a high-level plan that stays technically honest and actionable.

Relevant resources you can keep open while reading:

What success actually means for a CIO

A successful migration is not defined by how fast virtual machines are moved.

For a CIO or IT manager, success is measured after the migration, when the platform is already in use.

It means that production workloads run reliably on Vates VMS, with monitoring, backup and upgrade routines tested and documented. The operations team is able to manage the environment confidently, with clear runbooks and known escalation paths. From a governance perspective, licensing exposure is reduced and infrastructure costs become easier to predict and justify over time.

Just as importantly, there are a few conditions that should never be compromised.

A full “big bang” cutover only makes sense in very specific contexts. In most cases, a phased approach is safer and easier to control. Until the final validation is completed, a rollback option must remain available. Security and compliance requirements should also be validated early, not retrofitted once workloads are already in production.

Success comes from sequencing, validation, and reversibility, not from moving bits faster.

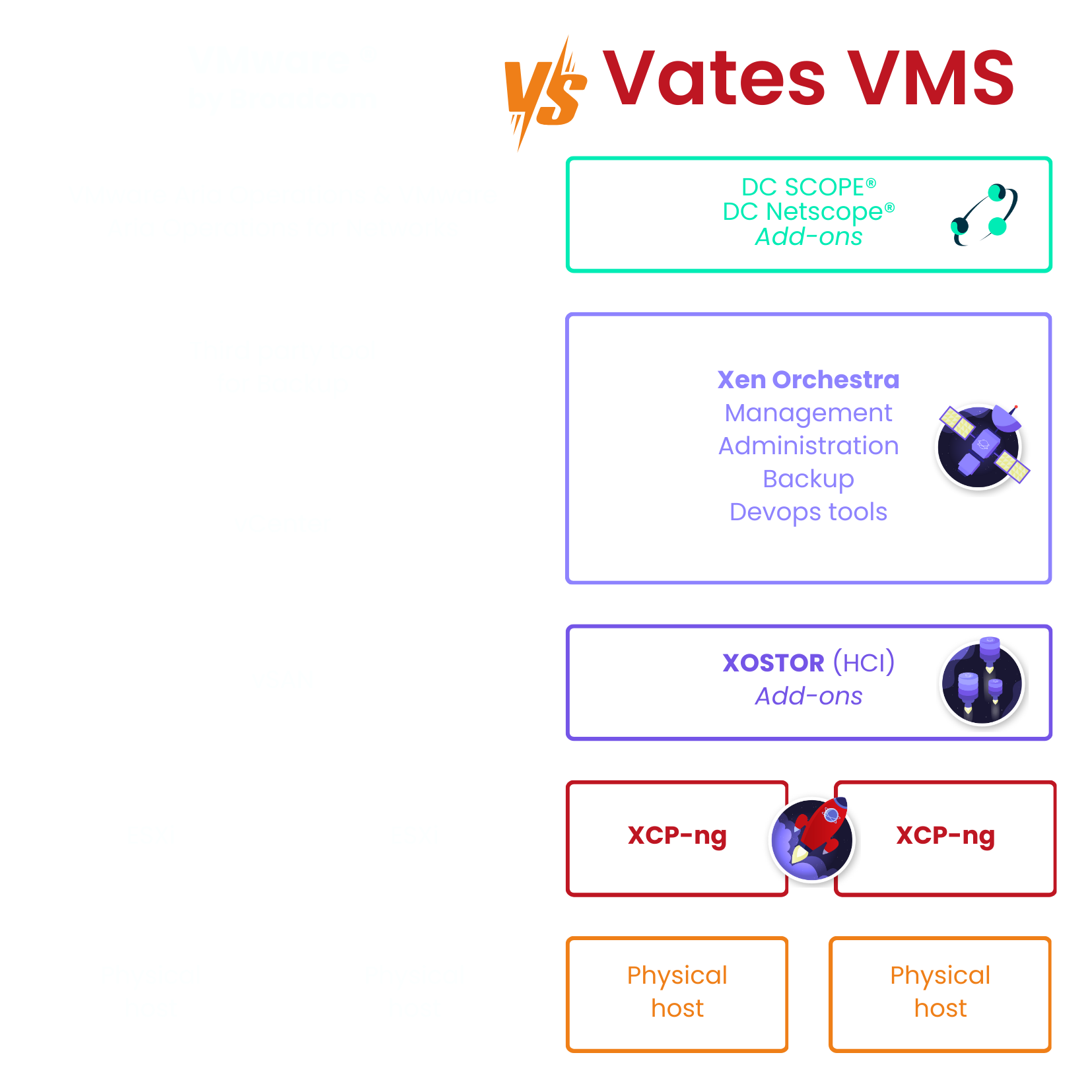

The platform view

Vates VMS is built around:

- XCP-ng as the hypervisor

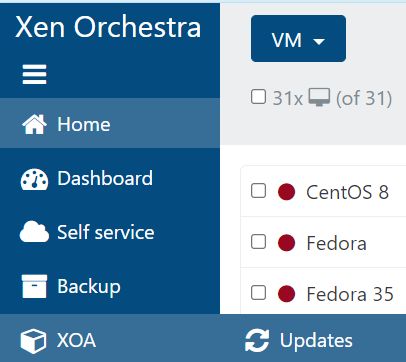

- Xen Orchestra for management, import/export, migrations, backups, and daily operations

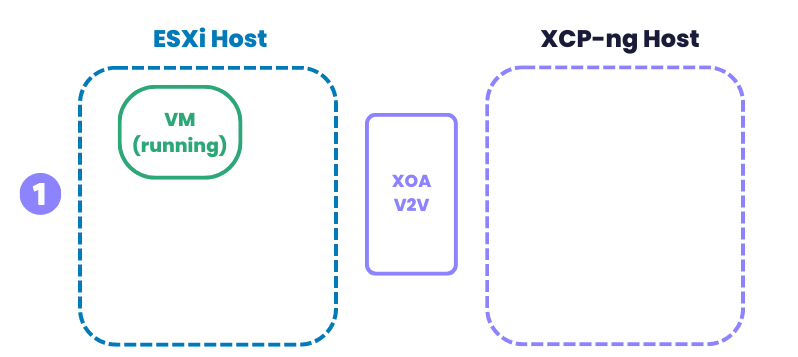

From a migration perspective, Xen Orchestra is where most of the work happens, including VMware to Vates V2V migrations .

Pre-migration: what you must inventory and decide

1. Inventory that matters

At minimum:

- VM list with criticality tier (Tier 0/1/2)

- OS and kernel versions, especially for legacy Windows and older Linux

- VMware specific features in use (snapshots habits, vSAN, VMFS version, etc.)

- Network topology expectations (VLANs, MTU, routing constraints)

- Storage expectations (IO patterns, shared storage needs, backup targets)

- RTO/RPO targets per application group

2. Decide the migration approach per workload group

You typically mix methods:

- V2V (VMware to Vates or Virtual to Virtual) via Xen Orchestra for most VMware estates

- OVA export/import when you want simplicity or when V2V is not the best fit

- Rebuild or re-platform for workloads that are better redeployed than migrated

VMware to Vates VMS: the pragmatic, low-risk path

1. What V2V is and why it matters

Xen Orchestra provides a V2V workflow designed specifically to migrate from VMware to Vates. The current approach relies on a dedicated migration backend that uses nbdkit and VMware VDDK libraries, with the goal of improved reliability and performance .

What you should take from that as a CIO

- It’s a supported path with documentation and known pre-checks

- It is not “magic”: VMware-side preparation still matters

2. VMware-side preparation checklist

The Vates migration checklist is blunt for a reason. Key items include:

- Uninstall VMware tools,

- Remove mounted ISOs,

- Control snapshots because they are expensive to handle in migration flows.

Also note the operational differences depending on your datastore type and version:

- VMFS 6 (vSphere 6.7+) requires the VM to be shut down for migration steps described in the KB

- vSAN imports require the VM powered off and specific handling (including direct vSphere IP access and temporary export location in some cases)

- NFS datastores can allow “warm migration” scenarios, with explicit remote naming requirements in XOA

3. Warm vs cold migration: what it really means

Warm migration, as defined by Vates documentation, migrates data up to the last snapshot, then stops the VM to migrate the snapshot delta. It requires at least one snapshot and permissions that allow the VM to be stopped .

That is the kind of detail a CIO should know upfront because it directly impacts downtime windows and business communication.

4. Recommended execution pattern

A safe pattern is:

- Pilot migration: migrate a representative, non-critical batch first

- Confirm guest behavior: boot, network, disk performance, application checks

- Define cutover runbook: exact steps, owners, timing, rollback

- Migrate by application group: not by “VM count”

The detailed step-by-step V2V procedure is in the official XO guide:

Hyper-V to Vates VMS: realistic guidance

There isn’t a single official “one button” equivalent presented in the sources above for Hyper-V, here is the most common approach:

1. Guest cleanup matters

Hyper-V environments rely on integration services. Before moving a workload out of Hyper-V, you should be deliberate about those services and how they’re enabled or disabled. Microsoft documents how to manage Hyper-V Integration Services via Hyper-V Manager .

Practical implication: you want the guest OS to boot cleanly and not cling to hypervisor-specific drivers or assumptions.

2. Disk-based migration is the common baseline

Typical flow:

- export or copy VM disks (VHD/VHDX, depending on your environment and constraints)

- create destination VM and attach imported disk

- validate boot mode and firmware expectations (BIOS vs UEFI is a classic pitfall)

- install the appropriate guest tools on the destination platform, validate network and storage performance

Where to anchor your internal runbook: start from XCP-ng’s “Migrate to XCP-ng” documentation, then adapt per OS and per workload tier .

The operating model: who does what, and how much effort it takes

1. Roles you need, even in a small migration

- Program owner (CIO or delegate): scope, risk acceptance, stakeholder comms

- Virtualization lead: target architecture, host pools, storage, networking

- Operations lead: backup, monitoring, patching, incident processes

- Application owners: validation sign-off per workload group

- Security/compliance: baseline controls, audit trail expectations

2. What drives workload effort

Effort correlates to:

- number of snapshots and datastore type on VMware side

- downtime constraints (whether warm migration is feasible and permitted)

- legacy OS, driver sensitivity, and application validation complexity and hardware‑related license validation for virtual environments

- network and storage redesign needs (if any)

This is why a pilot is non-negotiable for most environments.

Risk controls you should explicitly plan

1. Rollback strategy (per batch)

Define rollback before the first cutover:

- keep source VM intact until validation completes

- document rollback steps for each workload group

- define what “validation passed” means (technical + functional)

2. Change management

You need:

- freeze windows where appropriate

- a migration calendar visible to stakeholders

- clear go/no-go criteria for each batch

3. Data protection during the move

Even if you treat migration as “copy then cut”, you still need:

- a backup point you trust before migration starts

- clarity on where temporary exports or remotes are stored (explicitly called out in VMware migration checklist scenarios like vSAN and NFS)

When you want help: the supported services that map to real needs

If you want the migration framed as a predictable program (and not a best-effort internal project), Vates offers:

- Migration Package Service (POC guidance, migration strategy planning, dedicated expert during migration)

- Technical Account Manager (TAM) Service for ongoing guidance, readiness, upgrade planning, and long-term alignment

And if you simply want to start the conversation: the Vates contact page explicitly mentions assistance for migrations from VMware and Hyper-V .